Lemurs are Pollinators?! Un-bee-lievable!

June 17th through June 23rd is officially POLLINATOR WEEK! An initiative started by Pollinator Partnership, Pollinator Week encourages everyone to get involved in the discussion of pollinators and their role in the environment, as well as their direct impact on our lives. An estimated 35 percent of crops require some form of pollination (van der Sluujis and Vaage 2016), indicating that pollination is an incredibly important process in our food system alone, not to mention its impact on ecosystems. But what exactly is pollination?

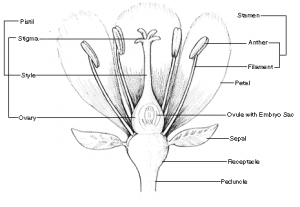

To understand pollination, we have to first understand what a flower is. Flowers help plants to produce offspring. While flowers can come in all sorts of shapes, sizes, and colours, most of them are made up of two essential components: the male part of the plant, the stamen, and the female part of the plant, the pistil (Raven et al. 2005). Pollen is made by the stamen and needs to travel to the pistil in order for the egg to be fertilized – this process is called pollination.

You may be familiar with butterflies, bees, flies, and wasps – but did you know that birds, bats, and lemurs are also pollinators? Dozens of species of pollinators can be found at McMaster. While you (probably) won’t find lemurs on campus, a pollinator can be anything that carries the pollen from the stamen to the pistil. Some plants are pollinated by wind, others by water, and many plants are pollinated by insects and animals. The traveller’s palm, Ravenala madagascariensis, appears to be mainly pollinated by the black-and-white ruffed lemur, Varecia variegate (fun fact: the McMaster Biology Greenhouse, located between Hamilton Hall and the Phoenix, houses two traveller’s palms). While the traveller’s palm benefits from the lemur carrying its pollen from flower to flower, the ruffed lemur uses the nectar as a food source (Kress et al. 1994).

So how do plants attract pollinators? Plants entice pollinators such as bees with offerings of nectar and, in some cases, the pollinator will eat the pollen, too (Raven et al. 2005). The plant benefits from assistance with reproduction, and the pollinator gets a tasty snack. In certain cases, the pollinator will even make a tasty snack – some species of bee make honey, which we can consume. Sadly, the beloved honey bee is not native to Canada or North America. As delicious as honey is, no bees native to this continent produce honey (Micalizio 2018). The honey bee is assisted through human intervention – so native bees and pollinators can’t keep up with the competition. The importance of native pollinators can’t be understated: native pollinators have uniquely evolved to work side by side with native plant species (Potts et al. 2016). When invasive pollinators and plants are added into the mix, plant and pollinator species can be completely wiped out.

Now that we understand how pollination works, we next ask ourselves “why should I care?” Do pollinators really matter, and is there anything that we can do to help? As a matter of fact – yes! By removing invasive species and allowing native plants to grow, we can help native pollinators, and increase the biodiversity at McMaster and in Hamilton.

Do you want to learn more about pollinators, or even see a pollinator garden? Pollinator Partnership provides lots of information on the identification of different pollinators, as well as their role in the ecosystem. Visit their website here. You may also choose to visit the Department of Biology’s Native Pollinator Garden on the east side of the Ivor Wynne Centre, or the Adam Chiaravalle Native Bee Nesting Garden beside the Indigenous Circle behind Alumni Memorial Hall!

References:

Kress WJ, Schatz GE, Andrianifahanana M, Morland HS. 1994. Pollination of Ravenala madagascariensis (Strelitziaceae) by lemurs in Madagascar: evidence for an archaic coevolutionary system? Am. J. Bot. [accessed 2024 June 18]; 81(5):542-551. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2445728. doi: 10.2307/2445728.

Micalizio CS. 2018. Honeybees help farmers, but they don’t help the environment [Internet]. National Geographic. [cited 2024 Jun 18]. Available from: https://blog.education.nationalgeographic.org/2018/01/29/honeybees-help-farmers-but-they-dont-help-the-environment/.

Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichhorn SE. 2005. Biology of Plants. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company Publishers. 686 p.

Potts SG, Imperatriz-Fonseca V, Ngo HT, Aizen MA, Biesmeijer JC, Breeze TD, Dicks LV, Garibaldi LA, Hill R, Settele J, Vanbergen AJ. 2016. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature. [accessed 2024 June 19]; 540:220-229. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature20588. doi: 10.1038/nature20588.

van der Sluijs JP, Vaage NS. 2016. Pollinators and global food security: the need for holistic global stewardship. Food Ethics. [accessed 2024 June 18]; 1:75-91. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41055-016-0003-z. doi: 10.1007/s41055-016-0003-z.

Article by Renee Twyford

Nature Stories